In this episode, Ron Stauffer interviews his Dad (also named Ron Stauffer), about a trip he took across the USA in 1980. On this summer journey, he rode a bicycle from the West Coast (California) to the East Coast (Virginia). His trip took 42 days, and he saw 10 states, and rode more than 3,400 miles.

This is a transcription of an interview recorded for the Ron Voyage! Podcast. Some of it may be difficult to interpret without listening to the podcast episode. Feel free to read this interview, or click on the link above to hear the entire episode. This transcript has been slightly edited for clarity and to correct grammatical errors.

Episode Intro: In today's episode, I'll be doing something slightly different. Rather than recount one of my own travel experiences, I'll be interviewing someone else who took a trip that I think is absolutely fascinating.

This episode is all about a trip my dad took over 30 years ago, where he rode a bicycle across the United States from the west coast to the east coast. Riding on a bike for more than 3,000 miles over a period of 42 days and seeing ten states in the process, it's one of the most ambitious trips undertaken by anybody I know personally.

As you listen to this interview, you will probably hear some road noise and dogs barking in the background since our conversation was held outside on the porch at his home near Orlando, Florida. But first, some background on our guest. My dad, who is also named Ron Stauffer, by the way, is one of the most interesting people I know.

Needing travel inspiration? Check out these free resources:

List: Best Travel Books

List: Best Travel Movies

Check back frequently as these resources are updated often!

His life story is filled with variety. He went to college at Cal State Bakersfield in California and earned a bachelor's degree in biology. From there, he decided to go to seminary and get a master's degree in theology. After school, he worked in several diverse industries. He spent nearly 20 years in medical sales, then was a general manager of a construction company and eventually served a few years as a prison chaplain at a Colorado correctional facility. Finally, he moved to Florida, where he now serves as the lead pastor of a church in Leesburg.

I think most people who know my dad think of him as a kind, humble man who is very deep and thoughtful. I also think that many people who meet "Pastor Ron" would be shocked to learn that the steady, unpretentious guy who faithfully shows up every Sunday morning has accomplished some remarkable journeys in the past that he wouldn't tell you about unless you asked him.

Like me, my dad is an explorer, thinker, and traveler, who ponders the meaning of life while journeying to new places. He has taken several trips that require sharp mental acuity and physical fitness, including camping in the wilderness in the Carolinas without taking any food or water, backpacking across Europe, spending half a year living in Germany and learning the language, and taking a bike trip across the country, which we'll talk about today.

To me, Dad's bike trip has always been something my family talked about, but it seemed more legend than truth. I've never really taken the time to learn about that trip, why he took it, how he prepared for it, or any of the other details. So in today's episode, I finally asked the questions I've always wondered about. If that sounds interesting to you, keep listening.

Ron: Hi, Dad.

Guest: Hey, Ron.

Ron: Many years ago, before I was born, you took a trip across the country on a bicycle.

Guest: I did.

Ron: You spent 42 days riding on a bicycle from the west coast to the east coast.

Guest: A most unremarkable bicycle.

Ron: So that was in the year 1980, right?

Guest: 1980, summer of 1980, yes.

Ron: And you started in California?

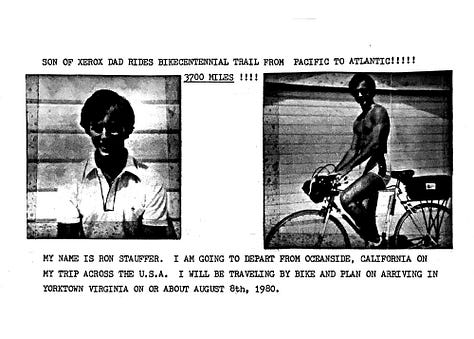

Guest: I started in Oceanside, California. I dipped my back tire into the water. There was a family strolling along the beach. I asked them to take some pictures with my camera, so we have some pictures of that. And I find it kind of remarkable to look at those pictures nowadays, the pictures from the Pacific Ocean, and then 42 days later, the pictures at the Atlantic Ocean. I think my thighs were twice the size at the Atlantic Ocean because I had put 3,400 miles under my belt by then, and those legs grew, baby!

Ron: Okay, so you left on Sunday, June 29th, 1980, and you finished what, August…

Guest: August 10th, 1980, 42 days later.

Ron: So, the first question that comes to mind is: "Why?" Why are you doing this? Why are you spending 42 days riding your bike from the west coast to the east coast?

Guest: Well, I had a strong sense of adventure from some previous adventures that I had done with traveling, some in America, and some over in Europe. And there was this Christian conference I wanted to go to in New York City that summer, and I just, I kind of played around in my mind with different ideas of how to get there. And just to really draw, you know, outside the lines—to color outside the lines. So I went back and forth, you know, shall I roller skate, run, walk, skateboard, and you know, I just kind of landed on: ride a bicycle. It's faster; it's overland, it's not motorized. And so I did that. Plus also, I had read this book by Peter Jenkins called "A Walk Across America." And man, I admired that guy so much. He thought that he would, you know, walk across America from the east coast to the west coast and said: "Hey, how hard could it be? I'll be done in six months, tops." Five years later, he finished his trip. But he had these great adventures along the way, and that intrigued me, and I thought: "I'd like to see America like not through a windshield. Not in an air-conditioned car." And my reasoning was: the more primitive you travel, the closer to the land you get, the closer to the experience you get. I had already had some experience in that, with backpacking through Europe the previous year and so, yeah, bicycle. Why not?

Ron: So you're kind of putting the cart before the horse. It was not that you were this insane cyclist who had done many, many trips on a bicycle, and you said: "The next thing would be riding from the west coast to the east coast." It was the opposite? It was that you said, I want to make this trip. I guess the bicycle is the best way to do that.

Guest: I didn't even own a bicycle. I was like; I don't think I had owned a bicycle for the previous, I don't know, seven or eight years or so. So I just thought: "Yeah. I'm going to ride a bicycle across the United States. I guess I better get a bicycle to do that." Right?

Ron: And it was an unexceptional bicycle. Or what did you say? An "unremarkable"….

Guest: Very unremarkable bicycle.

Ron: So you did not go to a bike store and say to a clerk: "I want to ride this thing for thousands of miles. Give me the best you got?"

Guest: Here's how I did it: I just had this picture in my mind of how much money I had and what kind of bicycle I wanted, and I kind of tempered one against the other and reasoned it out. And I thought: "I want a bicycle. I don't care how expensive the frame is." Now, frames are really a big deal. If you're in the bicycling world, it's a big deal. You can spend thousands of dollars on a frame, but I thought I could do a cheap frame, but I want really good moving parts. So I got on my knees, and I just said: "Lord, could you find me a bicycle that I can get with a really not-so-hot frame as long as it's lightweight, but really good moving parts," and "by the way, Lord, I've only got $100 to spend." So, long story short, I met up with a guy at work, and he had a bicycle for sale. What a coincidence, right? With a cheap kabuki Japanese frame and Campagnolo derailleurs, SunTour GT Luxe brakes, RIGIDA rims... I mean. The best moving parts there were. I asked him: "How much do you want for it?" He said, "I'll take a hundred." It's like he was listening in on my prayers. It was amazing. I added a few extra parts to it there, and I started working out with some buddies from college, and I sucked at riding a bicycle. I was so bad. They left me in the dust. We'd be out riding up these hills, and they'd be a hundred yards ahead of me. It was just like, it was embarrassing. I thought I was in good shape. I was in pathetic shape.

Ron: So to prepare yourself to ride across the country, you didn't like map out a plan and say: "For the next six months, I'm going to slowly build up my endurance," like a marathoner?

Guest: That would make sense! That would actually be very common sense. No, what I did is I spent about four weeks riding with these other guys, two or three times a week, and some early morning workouts, and they taught me how to ride a bicycle. And they taught me how to ride well and some techniques for building strength and so on. But really, I was at the mercy of just; I figured I would just get in shape while I was riding on the trip.

Ron: So, from the first time when you bought that bicycle to when your trip started, how long was that?

Guest: Not more than three months. Probably two months.

Ron: And how many miles do you think you rode on that trip?

Guest: I think on the trip, I rode about 3,400 miles.

Ron: So what, before that trip was the longest trip you had ever taken on a bicycle?

Guest: 30? (Laughs)

Ron: So from 30 miles to 3,400 miles in two or three months?

Guest: Probably, the longest training run I had done [before that] was 30 miles.

Ron: So the equivalent of walking around the block, then running a marathon, with almost no time to train in between?

Guest: Yeah, Probably something like that.

Ron: Okay. So 3,400 miles from the west coast to the east coast. How many states was that?

Guest: Well, let's see: California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia. Nine states right there. Did I miss one? I bet I did. [Note: forgot to add Illinois.]

Ron: So, it was about halfway between north and south? Central…

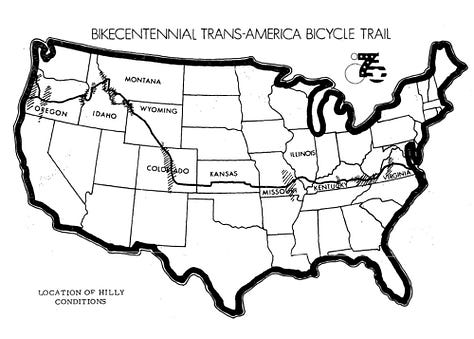

Guest: You know, I started out, there was a, there was a trail. Back then, we didn't have the internet. And so you, you know, how did you find information on: "Well, I wonder if somebody ever mapped out a bicycle route for other people to take?" and you just kinda had to go to the library and do your research there. There were no personal computers. There was no world wide web. So I figured this out in the springtime of 1980 and somebody had already done the heavy lifting on developing a—not developing a trail, but mapping one out that you could ride on and not get yourself killed on the trip, and it was called the Bikecentennial Trail. The idea being: "Hey, let's get a bunch of bicyclists together and ride across the country in 1976 for a celebration of the bicentennial of the United States of America." And so that was four years before I needed it. So I found out about this, and I sent in my $25 or whatever to their organization. They sent me back a box full of little booklets that showed, you know, okay, you go through this town and go through that town. Kind of like the book, the tour books, you know, Europe that—you'll laugh at the price. Back then, when I went to Europe, I took a book with me called "Europe On Five Dollars a Day," because you really could do Europe on five dollars a day back then if you were really careful. But, um, yeah, so I just followed those maps. And there were two basic trails: there was one called the Bikecentennial Trail that started out in [the] Seattle, Washington area, and went all the way across the United States by going down in a southeasterly direction to like Independence, Kansas and then straight east from there to Virginia. Well, I didn't want to take that northerly route. I already lived in California, so I thought, well, I want to start further South. So, they also had another map for something called the Southwest America Bicycle Trail. And that went from Southern California across the Southern United States and intersected with the Bikecentennial Trail in; I believe it was Independence Kansas. So I started out on the Southwest America Bicycle Trail. Took that for, what would that be, three weeks or so? Maybe three and a half weeks, and then joined up with the Bikecentennial Trail in Kansas.

Ron: So you mapped out your trip ahead of time.

Guest: It was kind of mapped out for me. Yes.

Ron: And did you say to yourself: "I will adhere religiously to this and do everything they say," or…

Guest: Absolutely not. That's not my way. It's a good suggestion. I'll follow it the best I can. I thought, and you know, sometimes, uh, there would be stretches where the map was not accurate. There'd be stretches where the road would be out, or there would be stretches where, well, they built an interstate on that old county highway. Now the county highway is gone, and here we are, we just have a six-lane interstate that doesn't even allow bicycle travel on it. So I did a little of everything. I tried to rarely break the law while I was riding, but you know, sometimes you just gotta do what you gotta do to get through the day.

Ron: Sure. Do you recall where you stayed each night?

Guest: I was digging through my stuff today, and I found my diary from this trip, and so... do I remember it off the top of my head? There's a lot that I don't remember, but as I was flipping through this diary and reading, it really brought back the memories, and I could start to see the people…. Of course, there were some favorite places that I got to stay. My dad worked with Xerox Corporation, and they had a network of offices all across the United States. And especially back then in 1980, it was a really big, popular corporation with sales offices everywhere. So my dad offered to call ahead to those different offices roughly along my route and say, "Hey, I got a boy who's riding his bicycle across the United States from the west coast to the east coast. You think you've got anybody there who could maybe give them a little hand, give him a place to stay for a night, maybe a meal?" And it was a pretty neat deal. I always took a pocket full of coins, you know, and would go to a payphone and call my dad almost every night and say, "Well, what do you got for me tomorrow?" He'd say, well, tomorrow, here's this Xerox business office, and call them, and there's a guy named Roy you want to ask for there. And he said he's got a place for you to stay. Great, Roy.

Ron: Oh, wow. So you didn't map out where you would stay ahead of time, so you would periodically check in with the home base and say…

Guest: That's right.

Ron: Okay, so grandpa, your dad, my grandpa, also named Ron Stauffer, by the way, was calling ahead as you were progressing? So maybe he had mapped out a little map himself and said: "Okay, so three days from now he might be in such and such"…

Guest: Oh, he was a logistics officer. He had a command post at home with a map of the United States up on the kitchen wall and little push pins in it and names and phone numbers, and it was amazing.

Ron: So, so, okay, how much did it cost? A trip like that, 3,400 miles on a bicycle. Did you save thousands of dollars?

Guest: That would make sense. Wouldn't it? Save thousands of dollars (laughs)? You got to understand what I was going through in my life at that time. I had recently become a Christian on March 17th, 1977, so I had known the Lord about three and a half years at that point. And I was on a very strong faith journey, with the innocence and the faith of a child, and I just believed that God would take care of me along the way. And I believed in my own toughness and resiliency and ability to figure things out, and I believed in my dad, who could help me find places along the way. And I believed in prayer, and I still do, by the way. So this was a really, you know, a strong formational point of my Christian life. And the whole thing started because I wanted to go to a Christian conference of the church that I had gone to for a couple of years. It was taking place that August in Brooklyn, and I just wanted to go out there. So I came up with this way to travel out there, and I just said to myself, "if God wants me to go on this trip, God will provide the means to get there."

Ron: So you didn't fundraise and ask for support?

Guest: No, no. I had a job at a drug store. And I saved what I could, but I had spent most of my money on my bicycle and some gear. I bought that bike for $100, put another $50 into it, got some gear for another $50. I think I had $200 into stuff to do the trip. And I started out with $82 in my pocket. After a couple of days, I got a traveler's check from my parents, which represented my income tax return, which had come home. I had my dad forge my name to cash my Income tax return That was like $100 or so, and he sent me a Traveler's check in the mail to one of the Xerox offices. And so there I'm up to $182

Ron: A whopping $182!

Guest: Yeah. Which, by the time I got that, I think I was in Texas. I had made it, you know, from California to Texas on $82. Now that includes my food. I never did once buy a room. But it included whatever food I bought and really, the most money I spent was on tires and inner tubes.

Ron: How many tires and inner tubes did you have to replace?

Guest: I never did count it up. I would guess. Fifteen inner tubes, maybe. And about eight tires, maybe.

Ron: Okay.

Guest: Yeah, they weren't cheap. You know when you're only living on $182, and you've got to buy a $20 tire, that's a big deal.

Ron: Is that how much it was? Wow!

Guest: They were—I don't remember the exact price…

Ron: But enough to put a damper on your budget?

Guest: It was several days' worth of food. Put it that way.

Ron: Interesting. Now you brought up an interesting point: you never paid to stay over on an overnight?

Guest: "It wasn't in the budget old chap!" It wasn't in the plans. No, I had a sleeping bag with me, and I had actually a youth hostel bed sheet from the previous year when I had traveled in Europe, so I had that, and I had a sleeping bag. By the time I got a couple hundred miles into the trip—and it was a hot, hot summer, there was a heatwave going across the United States where every new town that I arrived in, the newspaper headlines in the news racks that day said something like: "Six People Killed This Weekend in Record-Setting Heatwave." And so this heatwave went before me, and it cooled off just a little bit. By the time I would get to each city. So it was spreading from west...

Ron: You were following the heatwave?

Guest: I was following this heatwave! People were dropping like flies out there, and I'm out there in the middle of the sun, riding. So after a couple of hundred miles, I said, forget this sleeping bag thing. I finished the trip with nothing but a bedsheet. That was my sleeping gear.

Ron: So, no pillow?

Guest: I spent a number of nights outside, camping in a sheet, and I sent most of my clothing home. I had, you know, long pants and long this and that, and the other. By the time I, I sent all my gear home. I sent this box home. It must have weighed probably 12 pounds that I had been carrying. It had a sleeping bag and a bunch of my clothes, a spare pair of shoes and stuff. So I did the trip with one pair of Adidas running shoes. Two athletic shorts (gym shorts), two pairs of underwear, one tee shirt, one long sleeve tee shirt, a bandana, and that… I think that was it for clothing. That was my clothing. I slept in that, I rode in that, I went to church in that… I'm serious, and this is back when they had those really short shorts for men, you know, like REALLY short shorts, right from 1980. And I'm going into a Southern Baptist church and all the people going there are like, they're dressed up in these white shirts and tight ties and three-piece suits in the middle of the summer and everything. And I'm coming in in a really short pair of gym shorts and some Adidas, and I don't smell that great.

Ron: Sure, So how old were you at the time?

Guest: I was 22.

Ron: Were you still in school?

Guest: I was. I was 22—that should be the year that I would have graduated from college, but because I took a year off college to travel in Europe, what would have been my junior year. And because I slowed down a little bit and took a semester off to do some work to pay my bills and save some money for school. I got out of school in six years instead of four years with a bachelor's degree. So I graduated from college at age 24. So yes, so I had two more years of school to go before I would graduate.

Ron: But this was in the summer, so it didn't affect…

Guest: This was in the summer, so it didn't affect schooling at all. It affected my ability to earn money for school, [by] spending money, not earning it.

Ron: How did you afford the time off work? Did you, literally tell your boss, "I want to take a trip to New York, and I need 42 days off?" or how did that conversation go?

Guest: Yeah. I just went to my boss, Mr. Bruce Claussen, at Skaggs Drugstore on Ming Avenue in Bakersfield, California, 93309, and I said, "Uh, Mr. Claussen, I want to take the summer off. He said, "Well, I can't do that." And I said, "Well, I'm going, and I hope I have a job when I come back." And he said "Okay. You put it that way? I'll hold your job for you."

Ron: Wow.

Guest: Yeah.

Ron: So, okay, so you had a fan in your, maybe not a fan—a reluctant supporter in your boss. How about the other people you told? Or did you even tell people "I'm going to ride my bike all the way across the country?"

Guest: I told a few people. It's not something that I really wanted to publicize that much, you know? We're to let—the Bible says: "Let another man's lips praise you and not your own." And I just, I didn't know a whole lot about humility, but I knew it's probably not good to brag about something you haven't done yet. So I didn't, I didn't want to sort of puff up that adventure before it was accomplished.

Ron: Of the few people you tell, did anybody say: "What? Why?"

Guest: Not the people who knew me. The people who knew me were just nothing but encouraging cause they knew I could do it. Because I've basically always accomplished everything I've ever set my mind to. And those who knew that about me just said something along the lines of: "Yeah, that figures. I'm not surprised you're going to do something like that. I would never do it, but yeah, you can do it."

Ron: What about your parents?

Guest: Oh, they were all for it.

Ron: So you said: "I'm going to do this," and they said: "Okay?"

Guest: Yeah, absolutely. My dad and my mom were both—they were all for it. They were very encouraging. They had nothing but faith and believed in me. You know, Ron, that's what I grew up with, though. Both of my parents always encouraged me. [They] always believed in me, and they would always tell me: "Ron, whatever you set your mind to, I believe that you can do it."

Ron: And the fact that grandpa called ahead and got the Xerox crew on board to help you was obviously proof of that.

Guest: Yes. It was, totally. He was proud.

Ron: He was telling his friends and coworkers and people who worked for the same company that he'd never met before.

Guest: That's right, so in a way, the pressure's on, right?

Ron: Better not screw it up!

Guest: Right.

Ron: At some point along your Journey, people caught wind of, wow, there's literally a guy on a bicycle riding across the entire country. We should find out about his story. Can you share a couple of examples of that?

Guest: Sure. I'm trying to remember the names of some of these towns now, and I'm sure it's in this journal. There was one lady I stayed with, and I don't remember how I met all these people. Sometimes they were Xerox people; sometimes they were just people that I just met…

Ron: Like at gas station, filling up?

Guest: Yeah. Okay, so there's a gas station in Kansas, and I'm on the payphone out in front of this 7-11. I called my dad. And I said: "Well, dad, you got anybody for me here in this town?" He said: "No, I got somebody for you in the next town." I said: "Okay, great." He asked: "Where are you going to stay tonight?" I said: "You know? I don't know where I'm going to stay. I guess I'll look around here for a park or something, but I love you, dad, and I'll call you tomorrow and let you know that I'm okay." And there was a tall gentleman, a handsome fellow in a business suit, and he had just gotten off of another payphone there, and when I hung up the payphone I was on, he said: "Pardon me for listening in, but I overheard you talking to your father there. I'm (I forgot the fellow's name. Let's say his name is Bill Smith.) My name is Bill Smith, and I'm the president of one of the two banks here in this town. And my wife is the president of the other bank. So we're business people here, and we've got a nice place. And I just got off the phone with my wife, and she said, 'Heck yeah, sure. Invite that young man over to spend the night with us.' So we'd like to adopt you for the night." And so I said: "Sure!"

Ron: So the bank president at a city in Kansas that you'd never met overheard your conversation on a payphone and said, "My wife has invited you to spend the night in our house?"

Guest: "We'd love to invite you to come spend the night. Spend a few days if you want!" I didn't, you know, but they took me to their cabin on a lake or something, and we spent the evening, swinging off rope swings into the lake and barbecuing outside and, and I just enjoyed that. There are all these stories going all across the country. You know, what I learned is that the people of the United States, there's a lot of good, good people here with really open hearts and we don't share about those people enough. They're the salt of the earth, and sometimes you need to open your heart to strangers and accept some help from them; accept their hospitality. And don't be afraid to take a little risk that way. Now, I had sharpened my people-judging skills the previous year, backpacking and hitchhiking through Europe, going through countries where I didn't understand the language. And if I got my thumb out and I'm hitchhiking, and some guy pulls over and speaks to me in a language I do not understand, I have about three seconds to figure out whether this is a good ride or a bad ride, and I don't have any clues from the words being spoken because we don't even speak the same language. You develop some real survival skills that way. Real people skills when your life is on the line, and those kinds of skills—That kind of street-wise instinct did me very well in the business world, the world of commerce, the world of sales, and just… the street. I learned a lot about humans and human nature, and sometimes I met some people that were questionable, maybe not so honorable. But I've found ways to not get into trouble over that.

Ron: At some point on your trip, people in the media: radio, newspaper, folks like that caught wind of what you were doing and thought: "Hey, this is a good story. I'd like to share it with our public." Weren't you interviewed a couple of times?

Guest: I was. So, word would get around, maybe somebody would see me writing out on the highway, and that'd be 20-30 miles outside of a town and word would kind of, the buzz would start happening in the town there and they had time to prepare for me to come in. There was a time a lady came out who was associated with a radio station in Texas, and she offered me a place to stay. She was old enough to be my mom, you know, and I felt pretty safe there. So I got interviewed there on the radio and then got back into the car and went and stayed there and went to church the next day with that lady and, and you know, further… And then one news outlet talks to another and they read each other's stuff. And then I got to, by the time I got to this little town in the panhandle of Texas: Borger, Texas. And I wound up for somehow staying with a family there and they called the local newspaper. The guy came out and interviewed me, and took some pictures. It was a big excitement, you know, one of those towns where the newspaper comes out once a week, and it's about six pages long. Okay. So, like, this long-haired young guy from California, in very short shorts. He's big news, right? Big excitement in town. It's is one of those newspapers where they have half of a page dedicated to: "Well, the Lansings invited the Jennings over for dinner this last Friday night. Had stroganoff, I hear," so it's a big deal, but they're good people.

Ron: What was it you wanted on this trip? Aside from, okay, I've got a conference to get to in New York. Like in what way did you expect that a trip like this would change you or teach you something or shape you, and how did it actually do that?

Guest: I think that my expectations of what the trip would do to me and for me, were much lower than what the trip actually did for me and to me. I think I had low expectations. I thought it was going to be fun. I thought I would get in shape, and I thought I would get to see America. So it did all those things. I did not realize ahead of time; I could not imagine the impact on my spirit and the impact on my psychology and my faith life that this trip would have. I told you before that I started the trip with $82 in my pocket and 3,000 miles in front of me. I didn't really stop to think that much about what that means. Like that's, you know, that's a penny a mile or something crazy like that. I wound up leaning on God more than I ever imagined. I wound up needing to trust strangers to a far greater extent than I ever would have thought was reasonable or prudent. And to wake up, hours before the sun each day, and to see the sunrise in your face, (cause I'm going east) every day, generally along a quiet country road, you're so close to nature. It's a primitive form of travel, and you have eight to 10 hours a day alone with your mind to think about: "Why am I here?" and "What is my purpose?" And I think it formed a basis for what kind of man I would become. It was much more than just getting big thighs while riding a couple thousand miles and seeing America. The fact that I deliberately took on a challenge that I was almost certain was beyond my ability—this did more to build up my faith in my young Christian years than just about anything else I ever did.

Ron: And it sounds like a big part of that was meeting people that you could never have known ahead of time, that you bumped into at a gas station in Kansas?

Guest: Yes. And I got to see that regardless of their faith or their ideology or whatever, everybody is a human being. They all deserve a basic measure of respect, and we need not be afraid of everybody that we meet. I look around today. Then I see in the news and social media; I see a lot of hatred. I see a lot of mistrust between people, and that goes completely counter to my experience with people riding a bike across the United States. People who are different than me, who believe a little bit different than me; they're not my enemy. I can love them and respect them and live with them. Yeah, it was a spiritual thing. Getting to meet different kinds of people. I met people who were amazingly wealthy, and I met people who were really poor, and both were very giving and generous to me and just poured out their hearts to me. And so I learned that extremely wealthy people are not bad because they're wealthy. They can be absolute salt-of-the-earth, good, Godly, wonderful folks. And the same thing with people who are very, very poor. They have as much value as anybody who's really wealthy. And I know we learn that and we talk about that in Sunday School, and in college, and you know, wherever your circle of philosophy is, and discussion is. But when you get out, and you are living in other people's homes, spending the night there, they're cooking for you; they're helping you plan your next day's trip. You get to meet their families and their dogs and their, you know… I stayed with people in single-wide trailers. I had never slept in a single-wide trailer before. I grew up in an upper middle class, fairly prosperous lifestyle. And to go stay, for example, on an Indian reservation where everybody there either lives in an Adobe hut or a single-wide trailer, they're good people. It was a great experience.

Ron: What was the worst part of the trip? Was there a low point?

Guest: I don't remember one. I had a few negative experiences, but they didn't qualify to make it a bad trip or a bad day. It's just some negative things that happened. Not many, but a few that there's just, you know, that's just something you overcome, and you move on. Nothing that ever made me despair or say: "Oh, this stinks. I don't want to do this." No.

Ron: On a more positive note, we talked about what you learned about America; what you learned about people. What did you learn about yourself? I would imagine 42 days, essentially alone, coming into contact with other people, but essentially alone, you learned something about yourself on a trip like that.

Guest: Well, it reinforced in me the conviction and the confidence that also I, but I think, I mean everybody: if I really set my mind to something and I'm willing to sacrifice enough, and I'm willing to deal with some difficulties with a good attitude. Man, that'll get me through just about anything. Not to be braggadocious, but I think you can accomplish just about anything you really set your mind to if you just decide that's what you're going to do, and you're going to pay the price to get there. I'm not saying a person can do anything, but I'm saying if it's really important to you, here's what I learned for me: For me, if something's really important to me, and I'm willing to save up some money for it and do a little research about it and just like launch out and take a risk and try something… pretty good odds that it's going to go well. As long as I stay on top of my attitude…. I learned that about me. That I can pretty much—it's not because I'm special, I think it's within most people, but for me, I learned this about me—I can accomplish almost anything I set my mind to. I don't mean to be the positive of power of positive confession. I'm not into all that. But if you set an athletic goal, a financial goal, educational goal, and you sacrifice a few things to get there, you can pull it off. But also, I learned this trip enabled me to be alone enough in my own head. I learned that I like it there in my head. It's a good place to be. I like thinking about things. I like deeply contemplating the mysteries of the universe, the nature of God. I think it was the beginning of my journey to becoming an intellectual.

[Ad Break]

Ron: So you're on this trip. 40+ days, 3,000+ miles. It's over. It's done. It's the last day. What's going through your mind?

Guest: So I remember I had called my cousin Susie to come to pick me up there at the Chesapeake Bay at a certain Wharf. I was not going to finish the trip until she got there. So, you know, I had spent a couple of hours there waiting for her to arrive while I'm looking at the ocean, not completing it.

Ron: It's so close. It's so far away.

Guest: It's so close yet so far away! I gave her my camera, and said: "Hey, why don't you take some pictures of me as I ride my bike down into the ocean?" It was a little anti-climactic because—it sounds quaint to say—it wasn't about the destination. It was about the journey. The greatest part of the trip was not arriving at the Atlantic Ocean. That's not the purpose. The purpose was going—it was journeying there. And so for me, what I learned out of that, it was a metaphor for life. I mean, it really drove it home to me in a way that I could never have experienced otherwise, probably, which is, you know, an old-age retirement with a big house or something like this—if you live your whole life and that's your destination, "I'm going to build the dream house, and I'm going to have the woodshop in my garage and do all these things that I can, finally, when I have time, I can do all these things" and then you arrive and you go: "Huh. Maybe not so fulfilling." And you look back on your life, cause I'm getting closer to retirement age now. You look back on your life, and where's the real joy? It was in the hardships of being a 35-year-old father trying to bring home the groceries, and you get through these hard things in your life, and you forge relationships and love and family and friendships, and you suffer. And those are the good things of life, not going through the suffering, but coming out on the other side. And so when I finished this bicycle journey, little over 3,000 miles, six weeks, it was good to finish it, but it wasn't the high point in my life. And that was a real, I won't say it was a real let down, but it was a real "aha moment" for me, like thinking: "I should be happier than this. This should be a bigger deal for me. I should be just like jumping out of my skin to be here at the destination."

And I wasn't, it wasn't a letdown, it was, it was a pretty cool moment, but…

Ron: But it wasn't, the high point.

Guest: It was not the high point of the trip. And there wasn't any one real high point of the trip where I could say, like: "Oh man; this was the best day right here." I suppose the last day of the trip was a high point of the trip in the sense that I could look back and on a lot of experiences gained that made me who I am today and that that point more than any other point in that 3,000-mile journey. Then I could really appreciate: "Look what I have done. Look what I have come through. Look what God has done for me in all this. I'm closer to God. I know more about myself. I value my parents more than I ever did. I value family. I value the people of these United States. They're great, good people. This has been a great adventure. I'm sorry it's over."

Ron: So less about being happy that it's over and saying: "I did it; it's done." And maybe you felt more like: "I'm a little bit sad that it's done?"

Guest: I was. I was a little bit sad that it's done. Yeah. But from that sadness came a determination, Ron, that I want to keep doing this, not a bicycle trip, not big, high adventure, but a determination that I want to keep experiencing every day to the max and squeeze the maximum out of it that I can and be open to those little things like these little experiences that make the day, like when that snake slithers across the road that you're traveling on your bicycle in Arizona in the high desert. And I get off my bicycle, and I look at that snake and I poke it with a stick, and maybe I pick it up and play with it and go: "This is a gorgeous snake. Praise God. What beautiful nature this is." Or to see—you know, I remember seeing a reservoir in New Mexico. Oh my goodness. It's got to be the driest state in the U.S.! New Mexico is a dry, dry, dry state. And I came to this—in the middle of this dry cactus desert—there's this big reservoir. And I got out, and I went swimming. I don't think you were supposed to, but I did. And uh, and I realized: "Wow! Water is a beautiful thing." And to be able to cool off on a 105 degree day in the New Mexico desert, in this pool, and just these little tiny things that add up to where you say: "Man, in the rest of my life, I never want to lose sight of the joy in the little things in the middle of the day when I least expect them." Part of my philosophy of kind of going through life is: if I'm traveling, if I'm going somewhere or if I'm doing something and there's an opportunity to see something cool or to do something fun along the way… to stop, take the time, go experience the thing, and, like, put it in your portfolio of things that you've done now. For me, part of the joy of life is building this portfolio of memories and experiences of, "I did this thing in Puerto Rico, I did this thing in Germany. I did this thing in Arizona." And, not to get a notch on your belt, like "Look at me, what a great list of things," but they start to form who you are as a person. So I encourage anybody—especially anybody in the Stauffer family—if you have the opportunity to do something cool, even something that makes you a little uncomfortable, makes you stretch a little... costs you a little money, just do it. Then nobody can ever take that experience away from you, and you will be a richer person because of it.

Ron: That's great. That's very much in line with what I try to focus on in this podcast, which is travel the world, explore, and you will be changed in the process. You will learn things; you'll be a better person for it. Travel is painful. You get sunburn on your legs; you get blisters. You say: "This hurts. It's hard. It's difficult. Why am I doing this?" And you go home, a better person, and you love your wife more, and you're more thankful for your kids.

Guest: Which is why in 1987 when I took my wife, your mom, behind the iron curtain in communist eastern Europe to Czechoslovakia and Hungary, I was having a great time because I was stretching myself beyond my comfort zone, and I said: "Isn't this great? Look at all this oppression in these Soviet countries! There were Soviet Army people there and tanks!"

Ron: And she hated every minute of it.

Guest: Ron: And she hated it! And I was going like: "Look how great this is, honey! We're behind the iron curtain!"

Ron: Okay, so in closing, this is, it sounds like this was the most transformative experience of your life before getting married.

Guest: Hmm. This trip on the bicycle was probably the most transformative experience of my life before getting married. There's one more that rivals it, and that was outward bound in North Carolina. Especially the solo experience of sitting for four days and three nights under a tree, by myself, not eating food or drinking water, but only with my Gideons New Testament and my journal. Yes, outward bound as a 17-year-old, it taught me that there are things out there that I'm being pulled towards. That are both scary and attractive to me, and I have no idea where I'm going to end up, and I have no idea how I'm going to get there, and I have no idea what I'm going to do with my life, but it's going to be an adventure and somehow it involves God.

Ron: Okay. So what would you tell somebody else? Let's say a 22-year-old man who comes to you and says: "Hey, I want to ride my bike across the U.S.?" Would you just not tell him anything and let him learn it on his own, or would you give him very specific guidance about…

Guest: No, I would only want to encourage a guy like that, but I think before you launch out on something that is really out there, to at least some extent, you should know yourself. You know, this whole business of going out on these fantastic journeys or whatever, to find yourself. I think you should have a concept of who you are first before you go out to quote-unquote find yourself. I think it's dangerous to go out into the world, especially today. It's a more dangerous world today, I believe. I think it's dangerous to go out without some kind of self-awareness, self-knowledge. There's a certain, there's a level of I had, I had a pretty high level of maturity going out there. If I saw a young person who was really immature and naive, I would discourage them from this trip. I would only want to see somebody go on a trip that involves some risk if they have common sense, self-awareness, and are a fair judge of people because you're going to be putting yourself in vulnerable place out there. So you should have some skills in judging the character of others people. Uh, I would also encourage a higher level of danger awareness than what I exercise. I think some situations I got through by the grace of God.

Ron: If you had this trip to do over, there are at least one or two things that you would do differently that you've mentioned. What are those final thoughts where you say, I would, I would do this a little bit different.

Guest: I would stop a little more often. If I could do anything differently about the trip, I think it would stop a little more often and experience a few more things. I made the trip pretty athletic, so to keep up a 92-mile pace, for me, that was a pretty blistering pace. It's a lot of miles, and you know, without any support, didn't have a support vehicle or anything. So you're carrying everything by yourself, and I think I would do fewer miles per day, probably closer to 70 than 90. Okay. And I think that would be more enjoyable. I'd get a little more sleep. Uh, although, you know, I was 22, so what the heck? You know, maybe that was okay back then, but I remember even thinking back then, yeah, I think I would do it slower next time. So instead of 42 days, maybe make it 50 days or 55 days or something. Okay. And I really did enjoy taking a zero-day once in a while, stopping, and just hanging out, doing something fun.

Ron: Do you have any final highlights on a zero-day? Like things that you might have done when you weren't on your bike?

Guest: I did just hang out in Borger, Texas, with that family. I really enjoyed them so much, and I just took my bicycle apart piece by piece, and I just polished up every piece of it with a toothbrush and some comet cleanser, you know? And put it back together. Okay. It was just contemplative, restful, just talking with some good old Southern people and enjoying some good food. Man. I must have eaten every scrap of food they had on their table. One thing about a trip like this is like, I normally just eat like a bird. I don't eat that much. My goodness. I couldn't shovel enough food in my mouth on this trip. I think I calculated; I was consuming at least 6,000 calories a day. That's a lot of calories. So like I found myself in the position of sitting at a table and asking everybody: "You going to eat those mashed potatoes? Here, I'll eat them." You know, some of the high points were really just sitting down and taking a day with the family and enjoying it. There was this one lady, I forgot her name, in the, in the mountains and the coal mine and towns, some coal mine in town in Kentucky. Man, I just enjoyed staying with her. She was really old, and she lived, she was in a wheelchair, and it was like this little house. I don't think even there was electricity in that house. It was like kerosene lanterns or something. And she got up at like 3:30 in the morning. She was frying chicken for me from my breakfast. And it was just cool. And I just about died that day with coal trucks knocking me off the stinkin' road. But, um, it was really cool to stay with the, you know, just kinda hillbilly folks there. It was neat.

Ron: Nice people.

Guest: Good people. Good, good folks. Yeah.

Ron: Thanks for being here today, Dad.

Guest: Thanks for having me.

Ron: It's been fun.

Guest: It has been good. I appreciate the interview. I learned a lot about myself tonight.